Mimi Plumb unearths the darker side of the Golden City, San Francisco

British Journal of Photography

January/February 2022

Mimi Plumb, from The Golden City © Mimi Plumb

I am sitting in the light-flooded living room of Mimi Plumb’s second story, Berkeley flat, melting into a cozy, plush chair as she sits a few feet away on the couch. She is telling me about her first job, working for the Department of Housing, after receiving her bachelor’s degree from the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) in 1976. For three years, she photographed farm worker and Native American housing throughout California. The experience proved formative. “What I was seeing felt like band-aids and I think that politicized me,” she explains. “I started to think ‘how can we address these kinds of problems?’” These seeds of social concern informed her practice and conversations when she returned to SFAI for her MFA in the mid-1980s. Plumb recalls, “for serious discussions about the meaning of my work, its overriding content, my concerns, fears, and anxiety about what I saw in the world, I spoke with Larry Sultan. We often talked about what is to be done. Do images make change? Can images make change?” She continues, “for a lot of us, the 1980s were a very dark period in American history. There was not a lot of optimism. Being able to comment on the world with photography is what interested me.”

I first became familiar with Plumb’s work in 2018 when Oakland’s TBW Books published her first monograph, Landfall. Like Landfall, The Golden City—her forthcoming book published by Stanley/Barker—largely mines her vast archive of pictures made in the 1980s, the majority of which she made in and around San Francisco. “I do see Landfall and The Golden City as being from the same pool of images.” She pauses. “However, what this book leaves you with is very different.”

“The golden city” is among San Francisco’s innumerable monikers. “So, the title was in my head from the beginning,” Plumb says. “San Francisco truly is a golden city, but with an underbelly, which is where I lived and what I photographed in the ‘80s.” She lived in a small one-bedroom flat in San Francisco’s Bernal Heights, “a block above Highway 101, on a street of low to middle income residences accessed by a dirt road.” She reminisces, “I have distinct memories of the sound of the freeway and the view from my bedroom window of telephone wires. The light was beautiful though. Many of the photographs in The Golden City were made in my neighborhood.” Several pictures come to mind, where modest homes perch in the foreground, the sweeping views of industrial sprawl obstructed by overlapping power and telephone lines. Plumb primarily worked with a 6-by-7 medium format camera, regularly visiting the nearby Dogpatch neighborhood, Warm Water Cove (or “tire beach” as she called it), and the city dump, along with more exceptional outings, like twice attending San Francisco’s infamous Erotic Exotic Ball. “When I went out to make pictures, I didn’t go thinking ‘this is exactly what I’m looking for.’ I’d just go out and look. But I do think I focused on things that other people maybe didn’t see or think were important.”

As with many young people at the time, Plumb was wrestling with the unrealized, idealistic aspirations of the previous two decades, becoming increasingly radicalized by what she was witnessing in her community and beyond. “I felt like capitalism’s need for instant profits didn’t address issues like climate change or poverty,” she explains. “I wanted to make work about that. But I didn’t want to do it in any sort of obvious way.” The pictures in The Golden City are not documentary in nature, which one might expect from work questioning society’s maladies. Instead, Plumb’s deep-seated anxiety and dread around these unaddressed problems are reflected in her often-unsettling subjects and a distinctive aesthetic of unease, thoughtfully edited and sequenced to ominous effect in The Golden City.

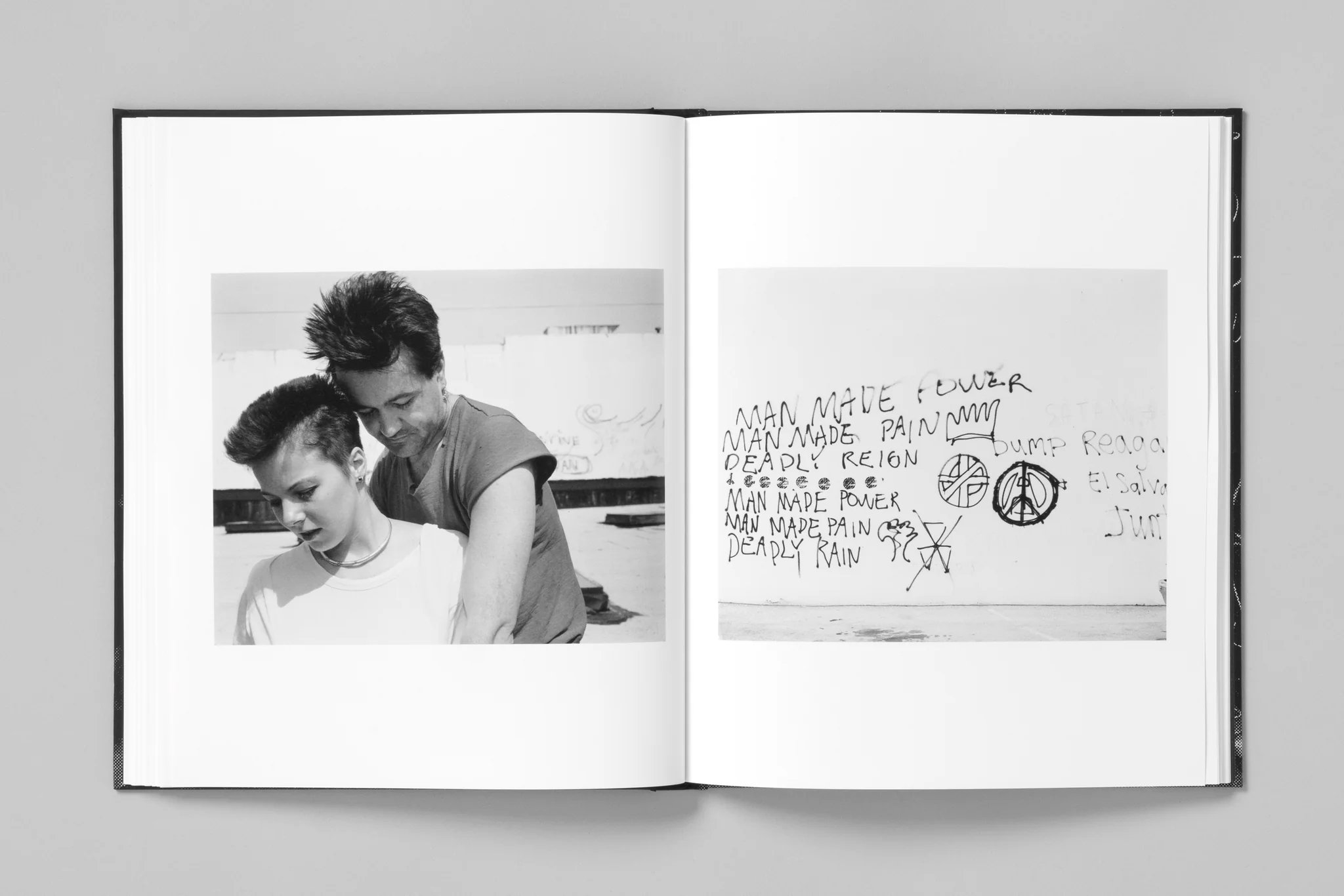

Burned out cars and buildings, mountains of detritus, high-rises mid-demolition, emptied freeways, graffiti-laden walls, abandoned schools, and lone figures populate Plumb’s The Golden City. Similar to Evidence (1977), a seminal project by her mentor Larry Sultan and his collaborator Mike Mandel, many of the pictures in The Golden City are enigmatic, inviting conjecture and eschewing certainty. What, for instance, are the trio of young people–all squeezed onto the floral sofa quaintly stationed atop a roof—staring at beyond the picture’s frame? And where is the infant that one would expect in the rolling baby chair? Or, what is a solitary billboard—emblazoned with Grant Wood’s seminal American Gothic—advertising amidst a desolate lot? Many of these pictures also evoke the work in Henry Wessel’s Incidents (2013), moments drawn from everyday life that subtly unsettle as one closely surveys the scenes. Plumb’s distinctive aesthetic approach and framing of the world further imbue her subjects with a psychological intensity, together creating a disquieting tension that compels sustained, curious looking. Even the most innocuous scenes—a construction site, a woman laying outside on a blanket, a teenager lost in thought on a stool—are rendered uncanny through Plumb’s lens. Her striking, nighttime portraits in The Golden City, where fill-flash is regularly used to dramatic, eerie effect, most acutely demonstrates this surrealism.

“What photobooks most influenced you back then?” I ask. Without hesitation, she replies, “Robert Frank’s The Americans. His sequencing based on content was my model for bookmaking. And it still seems to be my model.” It is not only Frank’s sequencing that resonates here, but also an interest in expressing an underlying position through the pictures themselves. Disparities in class, economic status, and power weave through both The Americans and The Golden City. Curator Sarah Greenough writes, “[Frank] wanted to express his opinion of America in his photographs and reveal nothing less than what he perceived to be ‘the kind of civilization born here and spreading elsewhere.’. . . he wanted a form that was open ended, even deliberately ambiguous—one that engaged his viewers, rewarded their prolonged consideration, and perhaps even left them with as many questions as answers.” A similar impulse underscores how Plumb made these pictures in the 1980s and her editing all these years later. Although the American social landscape evolved during the thirty intervening years, these two photobooks share an unequivocal sense of alienation, anxiety, and loneliness, sentiments intensified through the power of considered editing.

“I do have the book, just the pages though,” explains Plumb as she rises to open a cabinet on my left. She pulls out a thick, unbound version of the book from the printers. “The sequence in The Golden City follows my path in making the work” she tells me. “It's curious I wasn't aware of this earlier when we were working on the sequence since it's so obvious when I look at it now. The early landscape pictures are mostly from the mid-80s. The people/flash pictures were generally made in the later 80s.” Transitioning from day to night, you are shepherded by the book’s staccato rhythm through a tarnished vision of the golden city. The moment you think you have a foothold, you slip. Reflecting the apprehension Plumb grappled with at the time, disparate images weave together to create a visceral experience for the viewer. “It really says what I want it to say,” she reveals, smiling.

In The Golden City, rather than relying on the allure of nostalgia, Plumb artfully uses photographs made decades earlier to produce a fresh, relevant, and timely project. Despite San Francisco’s modern-day gold rush—the ever-expanding tech industry—many of the same problems persist; baring dated fashion cues, many of Plumb’s pictures could easily have been made today. And while the pictures are of San Francisco, the city is a metaphor for a much wider cultural phenomenon—both then and now. “I think that things haven’t changed that much,” Plumb sighs. “Except that some of the problems are worse today.” She emails me a few days after our conversation. “You asked me why I had thought my ‘80s work might someday gain attention. The main reason is the content remains so very relevant.