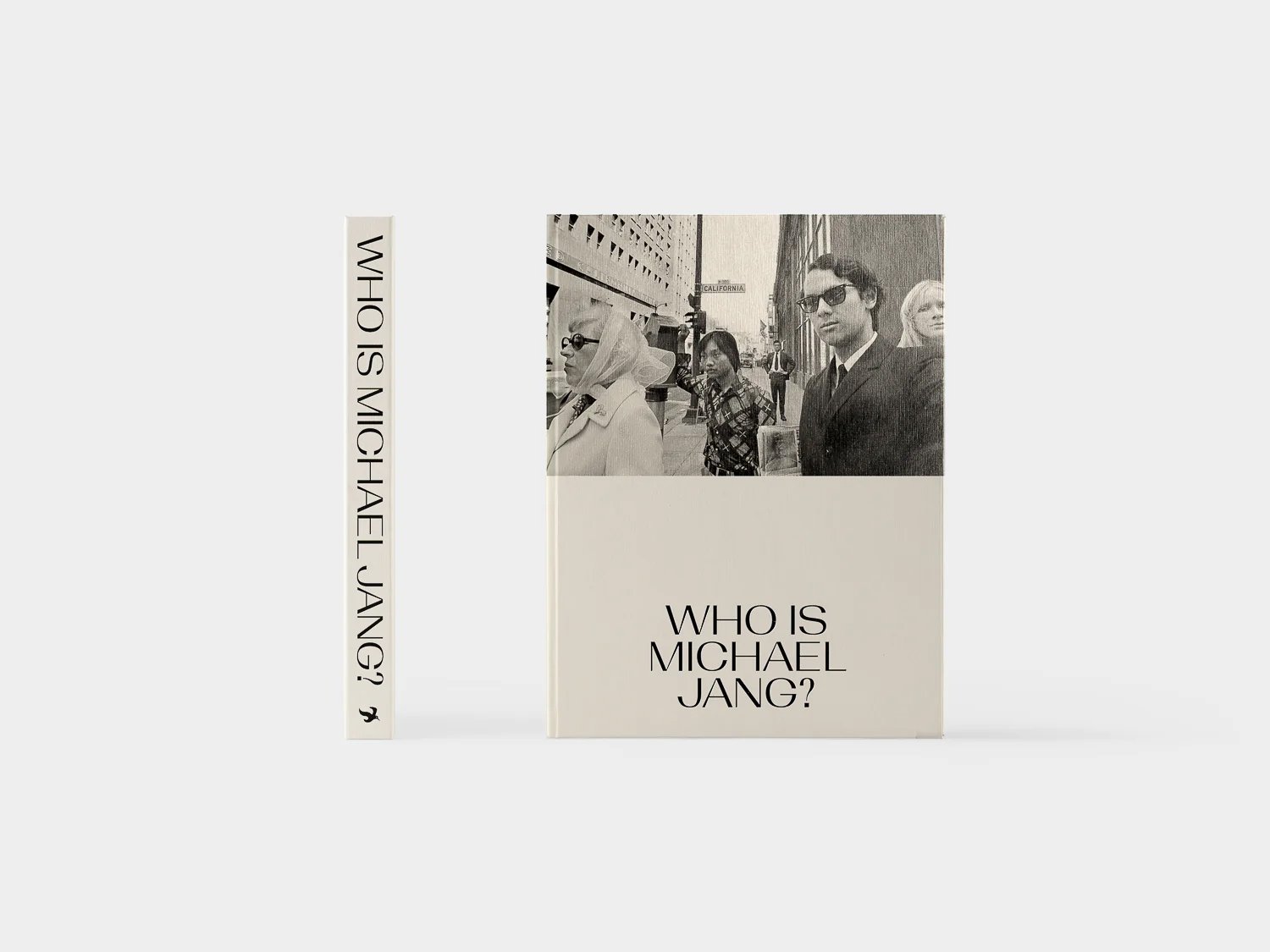

Who Is Michael Jang?

British Journal of Photography

October 2019

Michael Jang, Living Room Scene, 1973 © Michael Jang

In San Francisco—a city of nearly 900,000 people—I routinely find the six degrees of separation adage holds true. And in the case of photographer Michael Jang, there are a number of connections. I attended elementary school with his daughter and high school with his son. My master’s dissertation examined the distinctive environment at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) during the early 1970s, which was the same time Jang was studying at the Design School. And, I attended the opening of his first exhibition in 2013, an atypical gathering of young skateboarders and graffiti artists, art world colleagues, and his family members, several of whom I recognized—though forty years had passed—from the photographs on the gallery’s walls. However, despite all these connections, and even conversations with the artist, I know very little about him. I chuckled when I opened the preview of his forthcoming monograph titled Who Is Michael Jang?

When you walk into Jang’s home, you encounter a staircase on the left, a hallway straight ahead, and on the right, the first of two giant rooms devoted to his studio. “You give up a living room and a dining room. But better that than having to rent a separate space,” he jokes. The floor of one room is almost entirely covered by a stack of billboard-sized prints from Summer Weather, portraits of contestants auditioning to present the weather report for a San Francisco television station. He steps on them as I slowly follow behind, mesmerized by the photographs hanging along the room’s walls. We sit around a long refectory table as music plays from a nearby TV; although he lowers the music, it continues to hum in the background.

Though the vast majority of Jang’s “fine art” photographs were made during the 1970s and 1980s, they went largely unseen until 2001 when he fortuitously heard anyone could submit prints for consideration to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). “I pulled together some work from The Jangs and The Beverly Hilton,” he explains. “I was fifty at the time and I knew rejection wouldn’t hurt like it would have when I was twenty or thirty. By then, I was so far away from that work.” Instead of rejection, he was asked to come in for a meeting. Jang met with four curators including Sandra Phillips, now curator emerita of photography, who has become one of his biggest advocates. “They asked me, ‘where have you been? Because with this level of work, we would have seen it progressively out in the world.’ And I answered honestly. ‘I just took the pictures in school and then forgot about them for forty years while I got on with my life.’” In the intervening years, Jang worked as a successful commercial photographer, shooting everything from family portraits to magazine covers with celebrities, and focused on raising his children. “I explained to them that I never thought my pictures were any good.” He laughingly describes as Rick James wails in the background.

“So did you apply to CalArts with photography in mind?” I prompt. “Actually,” Jang interjects, “my first photo class ever was at CalArts (it was an elective) and The Beverly Hilton was my very first project.” He remembers, “we were mostly looking at big, gorgeous prints by Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and other f/64 photographers. I figured I would be lugging around a large-format camera too. Then, my teacher, Ben Lifson, happened to show some slides of Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand from the 1967 exhibition New Documents at MoMA, which were radically different. And I thought, ‘that’s what I want to do.’” And with that, Jang headed out on the streets of Los Angeles, with a borrowed Leica in hand.

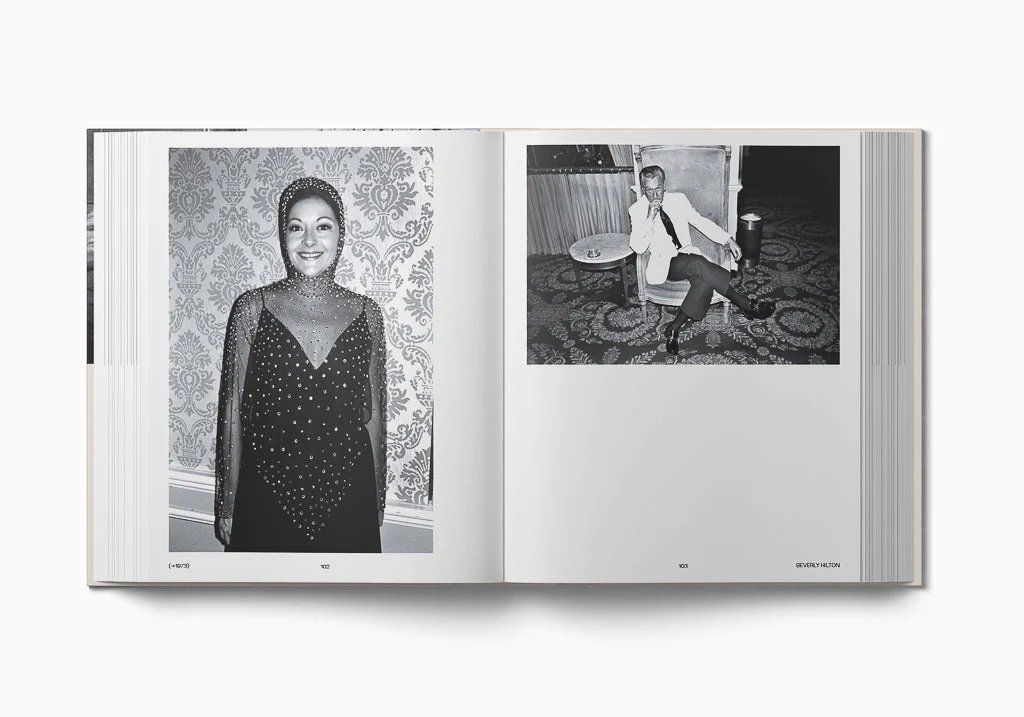

While out shooting one evening, the young artist stumbled upon David Bowie—swarmed by fans—in front of the Beverly Hilton Hotel. He quickly snapped a picture. As Jang meandered through the crowd, one autograph seeker stopped him. “’Did you know that there’s a major event every Saturday night at the Hilton? There’s a list posted in the lobby.’ And in my head,’” he recalls, “I think, ‘I’ve got a project here for the next semester.’” Jang’s The Beverly Hilton demonstrates the fledgling photographer’s fearless moxie—he even created fake press passes to gain entry to the hotel’s exclusive events. “The paparazzi used to call me ‘the kid.’ Sometimes, they’d call the police and tell them I wasn’t legitimate. But I figured I was a college kid, so what was the worst they could do to me?” Jang managed to photograph a number of celebrity icons: Jack Lemmon, Bea Arthur, Lawrence Welk, and even Frank Sinatra, coyly grinning as Ronald Reagan and Milton Berle applaud him as the March of Dimes “Man of the Year.” Other subjects are unnamed partygoers, striking not for their stardom, but rather for Jang’s mastery in framing and presenting the scenes before us. Moving quickly through his environment, he clearly considers all elements within the picture’s frame before clicking the shutter. In Two Couples at the Beverly Hilton, he catches two men, cigarettes held identically, while one date picks at her teeth and the other, barely visible at the photograph’s edge, mysteriously draws her hand to her lips. I am reminded of Winogrand’s work from the Centennial Ball at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1969. Photographer Tod Papageorge’s keen observation about those pictures could just as easily be said of Jang: “[f]or what he has given us is a unilateral report of how we behaved under pressure during a time of costumes and causes, and of how extravagantly, outrageously, and continuously we displayed what we wanted.”[1]

In the summer of 1972, Jang headed north for a summer class with Lisette Model at the University of California Berkeley Extension. “I thought I was going to do street photography. But I would often go hours without seeing something worth shooting,” he reveals. Instead, he decided to focus on the relatives he was staying with just outside of the city. “I’d done the thing where you go in, get the shot, and leave. This time, I went in deep. The difference is, when I look back at the work, you see that they are not guarded. You have to live with people to get those kinds of shots.” Jang followed family members throughout the day, at home, and during outings, his camera and flash at the ready, often right in their faces. Through the unique and yet universally relatable experience of his Chinese-American family, he documents the birth of suburbia. Whether it’s Aunt Lucy meticulously watering her garden at night or the family, all together in the living room, each absorbed in their own worlds (including the dog), sensitivity and humor permeate each subtly framed picture, reminding us of our own family pictures while transcending the snapshots in our own albums.

Jang entered straight into graduate school at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) after finishing at CalArts. “I needed a couple of years to figure out what I was doing and I also thought I wanted to be a teacher,” he explains. Like his fascination with the Beverly Hilton in LA, Jang soon discovered his newest subject: San Francisco’s emerging punk scene. “I wasn’t part of the scene, but I used my camera to get in. And I wasn’t so much into the big names; I was into the energy.” Documenting everything from impromptu concerts at school (“they would have concerts in a painting classroom, protecting the paintings on the walls with black plastic”) to more well-known groups such as the Ramones and Sex Pistols, his photographs not only bear witness to the music, but also the Punk movement’s distinctive atmosphere and culture.

In short, Jang was incredibly prolific at CalArts and SFAI. And I only touched on what will be included in his upcoming exhibition and publication. Even then, however, we will only experience a slice of what he shot during that time. Jang’s eyes well up as he quietly says, “I threw away more than half my stuff. I trashed it because I didn’t believe in it. I only kept about 250 rolls. And look at what I have. Compare that to the reported estimates of the archives of Vivian Maier—100,000 negatives and slides—and Winogrand—over a million negatives and 10,000 rolls of undeveloped film.” He pauses to wipe his face. “It’s just been hard this last year as Sandy has been going through my work because it’s made me realize how much more this all could have been. At times, I have an overwhelming sense of regret, but I am thankful that I have what I have. With the book and Sandy basically doing a retrospective…it’s enough.” He cracks a slight smile as he sips his coffee.

Michael Jang’s California—the photographer’s first major solo exhibition curated by longtime supporter Phillips—opens at the end of September at San Francisco’s McEvoy Foundation for the Arts. The first works visitors will see in the exhibition are not Jang’s, but a selection of prints by Arbus, Friedlander, and Winogrand. “Sandy and I decided it should start with a version of New Documents using works from the McEvoy Family Collection; this sets the tone for the rest of the show.” The second—and largest—room will be devoted to prints Jang made in school, suggesting the ways his work continues within the New Documents lineage. Larger contemporary prints will occupy the space that follows. And then, in the final room, “all hell is going to break loose,” Jang says with a wide grin on his face. “It’s going to be absolutely modern, using wheat paste, graffiti, Instagram. That area will look like nothing else. The exhibition as a whole will trace forty years of the way images have been presented.”

Launching concurrently with the exhibition is a monograph published by Pascale Georgiev and Kingston Trinder of Atelier Éditions, collaborators Jang has worked with on several zines in the past. Who Is Michael Jang? is a cleverly and thoughtfully sequenced tome that plays with scale and smart image pairings to vary the rhythm as you move through the six sections of plates, spanning 1972 to 1987. It sets itself apart from the majority of retrospective monographs; pictures are favored over text (there are only two short essays in addition to modest paragraphs that introduce each section). By focusing our attention on the work, Who Is Michael Jang? offers us the best vehicle for learning about the artist; the photographs say it all.

Surreptitiously tucked in a pocket on the back inside cover of the book is a small paperback, the angelic face of teenager with a big Band-Aid pasted across his forehead peeking out. Like Jang’s zines, the saddle-stitched insert is playfully laid out, layering images and bold swaths of color. Unlike the preceding pictures, these photographs are made much later (2001) and in color. Once again, Jang gained access to a scene of which he was definitely not a part: the underground high-school music scene in the Bay Area. Trailing his adolescent daughter, Jang captured the aspiring rockers not only mid-practice and performance, but also during the in-between moments. In one striking spread, a boy forcefully strums his electric guitar, his head pulled back, mouth open, and eyes closed. A girl seated on the ground looks up at him adoringly, hands clasped across her chest. Though the scene is contemporary, the dynamic captured—his wholehearted investment in the music and her admiration—feels timeless. On the opposite page, five shirtless teenage boys pose in front of a white wall. Though they gaze with confidence directly into the camera’s lens, their young bodies—and the requisite self-consciousness that accompanies this age—belie their “hardcore” message. Jang simultaneously captures a moment within a certain era, while revealing the perpetuity of shared human experiences.

Although some of this work has been seen in the past, much of it is being revealed for the first time in the exhibition and monograph. For an artist who has spent much of his life flying under the radar, this moment of recognition has Jang wondering what people will think of the work. “I don’t know how the photographs will be received. They are decades past their “sell by” date.” We both laugh. “We will see what kind of shelf-life they have. Maybe they’ll be like Twinkies and they’ll last forever.”

[1] Tod Papageorge in Garry Winogrand: Public Relations, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1977.