New Zealand’s Mongrel Mob Gang, photographed by Jono Rotman

British Journal of Photography

January 2018

Jono Rotman, Toots King Country.

Jono Rotman, Triple J Notorious’ Smokey, Waipawa. © Jono Rotman.

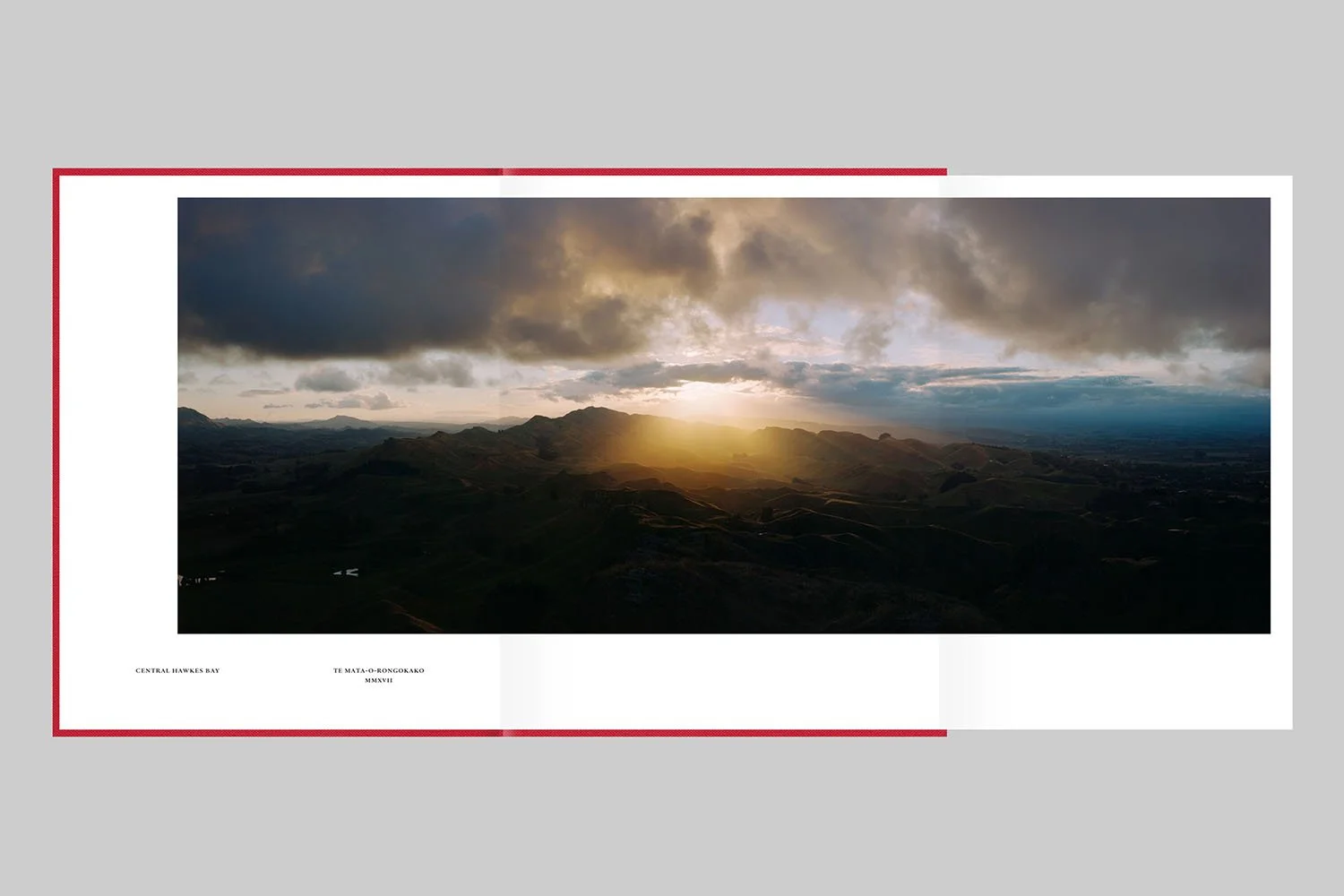

Arresting. Exquisite. Gripping. Chilling. Disgraceful. Unacceptable. These are all words people have used to describe portraits made by Jono Rotman. Created over the last decade, his project Mongrelism presents an intimate look at members of the Mongrel Mob—New Zealand’s largest, most notorious gang. Though he is looking at a subculture as an outsider—a domain regularly mined by photojournalists—Rotman eschews a traditional documentarian approach to his subject matter. In so doing, the project’s scope extends beyond the Mob itself to touch upon issues related to New Zealand’s charged colonial past and self-professed biculturalism, the politics and ethics of portraiture, and the intersections of seemingly disparate human experience.

Since childhood, the New Zealand born photographer explains, “I always felt certain violent and uneasy forces within my country.” In Lockups (2000–2005), Rotman photographed the interiors of prisons and mental hospitals throughout New Zealand, exploring the medium’s ability to convey the fraught “psychic climate” embedded in these state-controlled institutions. The works are eerily devoid of people, a deliberate decision made, says Rotman, “because I wanted to encourage a direct, personal interaction with the spaces. With prisons, for example, as soon as you introduce people into the picture, it becomes easy to think, ‘here’s the storyline: this place is for those sorts of people. And I can fit it all into my established worldview.’” By removing such easily construed markers, Rotman forces the viewer to engage closely with the details that are present, considering what those visual cues convey about what it feels like to be incarcerated and, perhaps also about New Zealand past and present, and the nature of culturally ingrained predispositions.

Following Lockups, Rotman “was thinking about male power and the extremes of how that is presented in the human experience.” He remembers, “on the one side, you have established modes of corporate, military, and state control. For me, ‘gangism’ is on the same spectrum of group adherence). Only with gangs, it’s committing to something beyond the established social ecology.” Through contacts suggested by a gang liaison within the police force, Rotman initially planned to photograph members of various New Zealand gangs; estimates indicate there are twenty-five gangs on the small, islands nation, with a total membership that outnumbers the country’s own army.[1] “It is a fertile subject,” he explains. “But for me, the Mongrel Mob ultimately felt like they have the most unique identity, the most searing percolation of the forces at play.”

Since emerging in the early 1960s, the Mongrel Mob has grown to over thirty chapters with a carefully developed and fostered reputation produced through committing some of the country’s most notorious crimes.[2] Early members describe the group’s inception as a response to the poor treatment and abuse they endured while in state care. Although the founding members were primarily white, the majority of today’s Mob members are Maori—the indigenous people of New Zealand—a group that has, despite proclamations of shared sovereignty since the nineteenth century, suffered continued and disproportionate marginalization and subjugation. The inequity and discrimination experienced by many of the gang’s Maori members has also fueled the Mob’s evolution. Mongrel Mob members typically wear red and black, and are identified by their elaborately tattooed faces. These tattoos usually feature a combination of the gang’s name, it’s symbol—an English bulldog, sometimes donning a Second World War-style German helmet—and the swastika. This loaded iconography emblazoned across their faces reflects both an aggressive response to their feeling of long-8gvstanding mistreatment—by the government of young men in state care, by British colonizers of indigenous Maori—and the gang’s commitment to offending mainstream society through a generalized “fuck you” ethos.

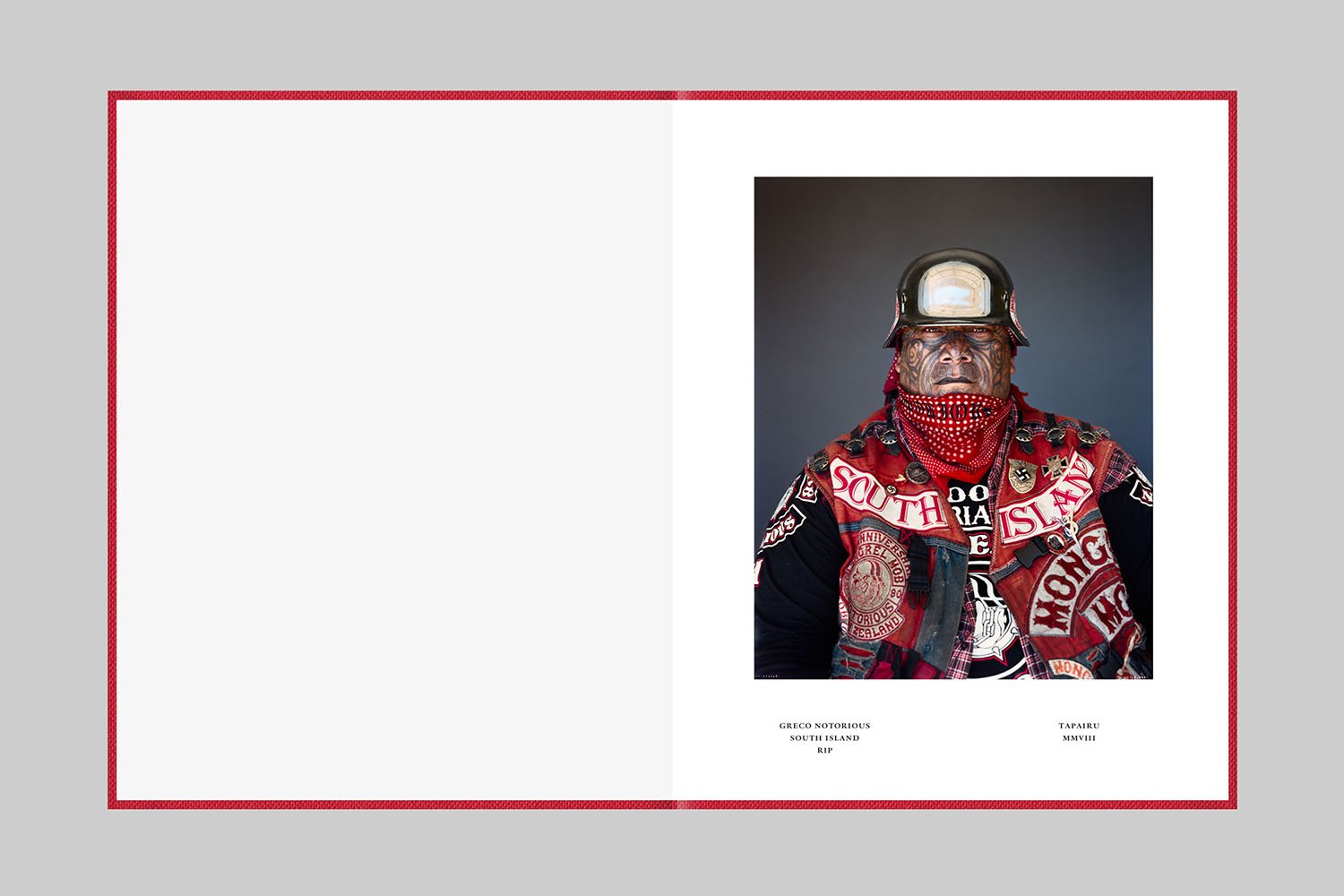

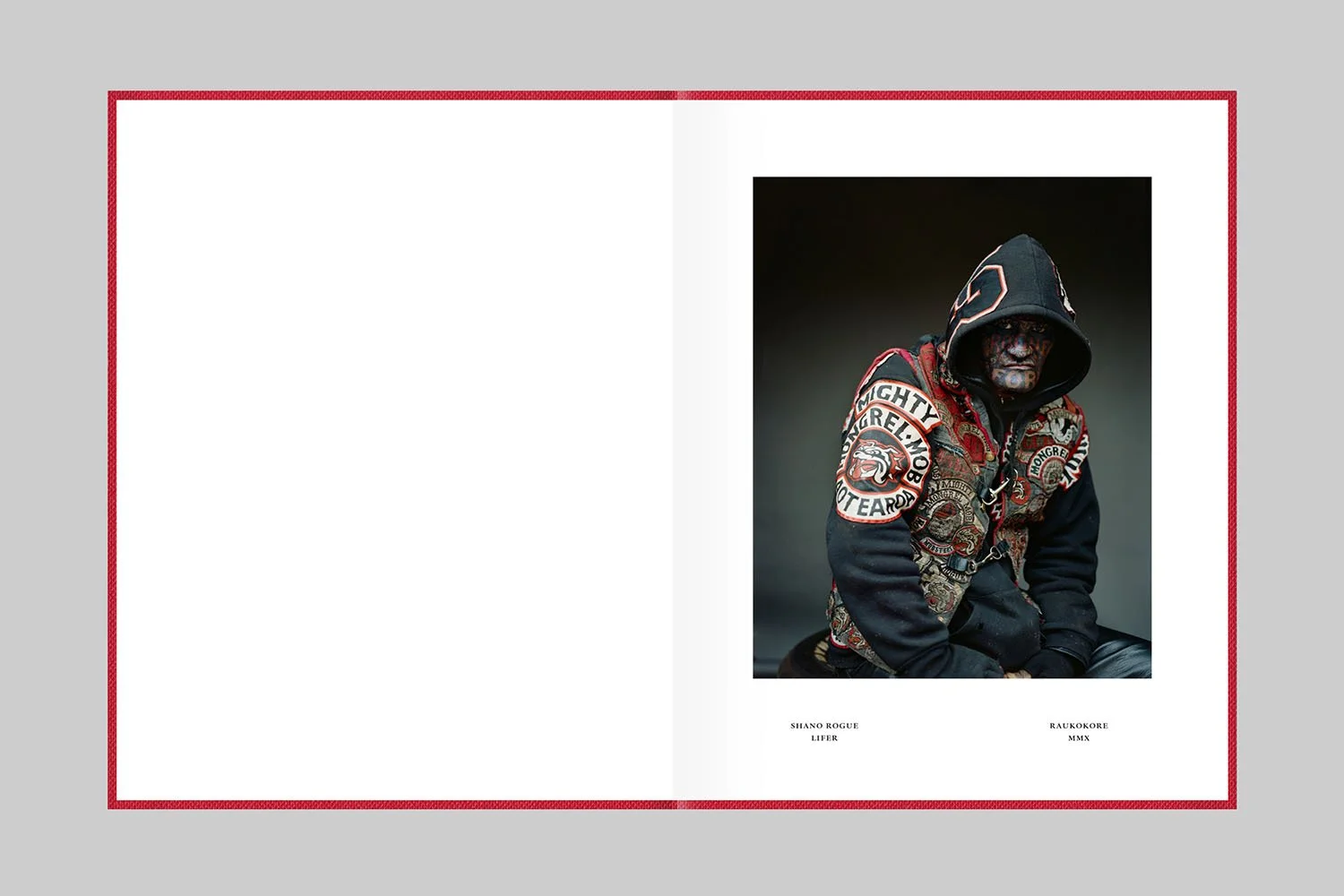

Though this charged backstory provides an intrinsically fascinating human-interest narrative, Mongrelism resists this reading in favor of something with greater nuance and wider relevance. From the start, Rotman aspires to refrain from a subjective exploration and interpretation of the Mongrel Mob in favor of “transmitting their spirit whilst still letting them retain their mystery and privacy.” He made the first portraits in a formal studio space with strobe lighting. The results, however, troubled him both aesthetically and morally. “Using strobes anesthetized their breath and the portraits seemed to lack a certain soul,” he recalls. “Also, there was a whole lot of tricky cultural precedent that began to dawn on me. In the studio, it felt like there was an incorrect power dynamic.” He opted instead to go to them, shooting the men in front of a plain backdrop at their homes using only the available, natural light. Rotman’s decision not only created a more challenging environment for shooting, but also altered the experience of the shoot for his sitters. “Because I’m shooting large-format with natural light, the process is really slow,” he explains. “So I have to give them a preamble—‘you’re going to sit. Then I’m going to focus and mess around with the camera, and you can’t move.’ It creates a ceremonial process which, in effect, takes us both out of our roles.” The resulting portraits attest to a relationship of mutual trust and understanding.

The unprecedented trust and access given to Rotman by this secretive group is echoed in his sense of responsibility to his subjects and their communities, a notable deviation from troubling examples of exploiting people seen as “other” throughout photography’s history. “Because of their trust and what was being gifted to me in their engagement, I have a responsibility to them that the work is not something that I just take away from them. The project’s relationship to them is really important to both the spirit and power of the work.” Rotman and Mob members jointly developed a protocol based on transparency and sharing; he shows them work in progress and discusses how he plans to carry it out into the world. While it has not always been easy to stand steadfast when his artistic integrity is in potential jeopardy, Rotman firmly defends the intimate involvement of the Mob in the project’s evolution. The work is far stronger, he explains, because “it carries the weight of their presence within it.”

Rotman’s portraits do not indiscriminately corroborate the mainstream dialogue about the Mob, but rather complicate widely held views. “The idea was that they would be arresting images because of the iconography and aesthetic qualities of the gang, but once you’ve been drawn in by that, you’d be forced to contend with the weight of human experience and whether the experiences of those men can be read into the topography of their faces.” His completed portraits, presented as detailed, larger than life-sized color prints, do just that. An uncomfortable tension between aversion and seduction elicits a visceral confrontation with the work. The immediacy of their conspicuous and, at times, fearsome appearances disconcert the viewer. We see unnerving tattoos, disquieting expressions, patch-laden clothing, and other gang-related insignia. And we can surmise these are men who have supported and/or committed terrible crimes, and likely had them visited upon themselves. Among my first questions is why? Why have these men, for several generations now, continued to turn to this particular manifestation of community? Why is mainstream integration untenable to them?

Like the vacant spaces in Lockups, these photographs are void of context beyond the lone subject, leaving the viewer to grapple with the available information and details. They recall Richard Avedon’s In the American West, where his outsiders were positioned in front of blank backgrounds so that “[n]othing competes with the presentation of their poor threads, nothing of the personal environment, nothing that might situate, inform, and support a person in the real world, or even in a photograph.”[3] As we continue to look closely at Rotman’s sitters, subtleties start to reveal themselves: age, distinctive facial features, tones of flesh, and the quality of their postures, gestures, and eye contact. Though formally deadpan, there is a sensitivity characterizing Rotman’s depictions of his Mongrel Mob subjects, one that encourages viewers to confront the difficult truth of our shared humanity. And it is this unexpectedly tender view of a nationally villainized group that underscored the polarizing reception of the work during its first major exhibition in New Zealand.

In 2014, eight of Rotman’s Mongrel Mob portraits were shown at the Gow Langsford Gallery in Auckland. The exhibition garnered heated public debate and media criticism, especially given that one of the included subjects—Shano Rogue—was then on trial for murder with the alleged victim’s father pleading to the gallery and artist to remove the photograph. A spokesperson from an anti-crime advocacy group deplored the work, asserting “I think it is glorifying gang culture and completely offensive to their victims, and the members of the public and society who live a socially acceptable and tolerated life.”[4] What lies at the heart of this argument is who deserves to be photographed and in what way. Should individuals we might otherwise turn away—those living socially “unacceptable” lives— be excluded from photographs? Rotman intimates, “it’s OK to see a black-and-white, documentary photograph of someone from a difficult environment because that representation fits into the way they’re codified within the mainstream narrative.” His photographs resist the expected; they do not recall police mugshots or National Geographic-style, ethnographic studies of faraway tribes. They bear a stronger resemblance to nineteenth-century portrait paintings. They are dignified portraits impelling viewer introspection about the source of his or her discomfort and confronting the belief that art is bad or amoral because it triggers uneasiness or indignation. After speaking in person and at length with Rotman, the victim’s father understood his unpopular decision to leave the photograph on view: “It’s his work of many, many years…. He is not a bad man, one of the best I’ve met. He sticks to his values. He doesn’t compromise his beliefs. I’ve learned a lot. Hopefully I’ll come out a better man.”[5]

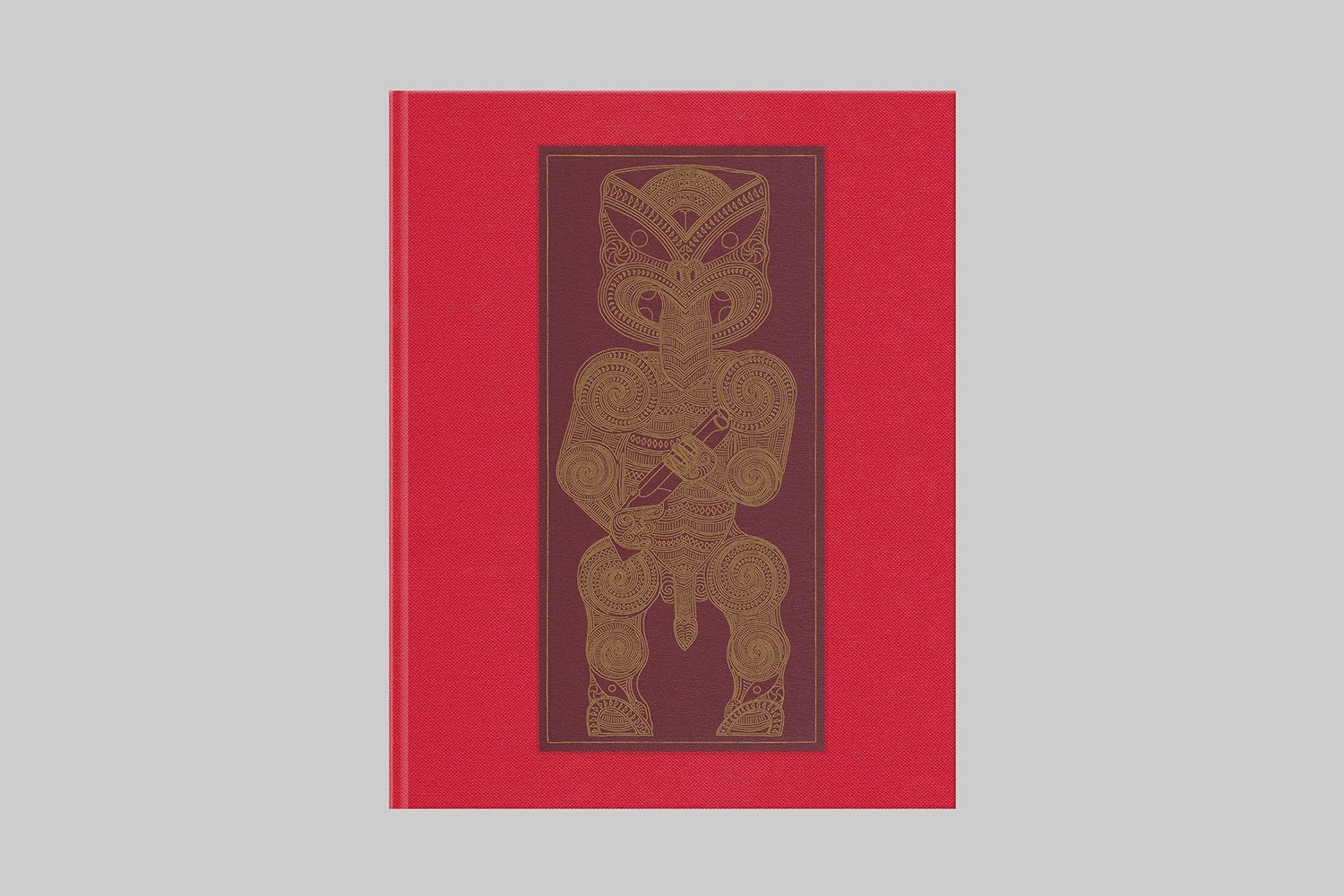

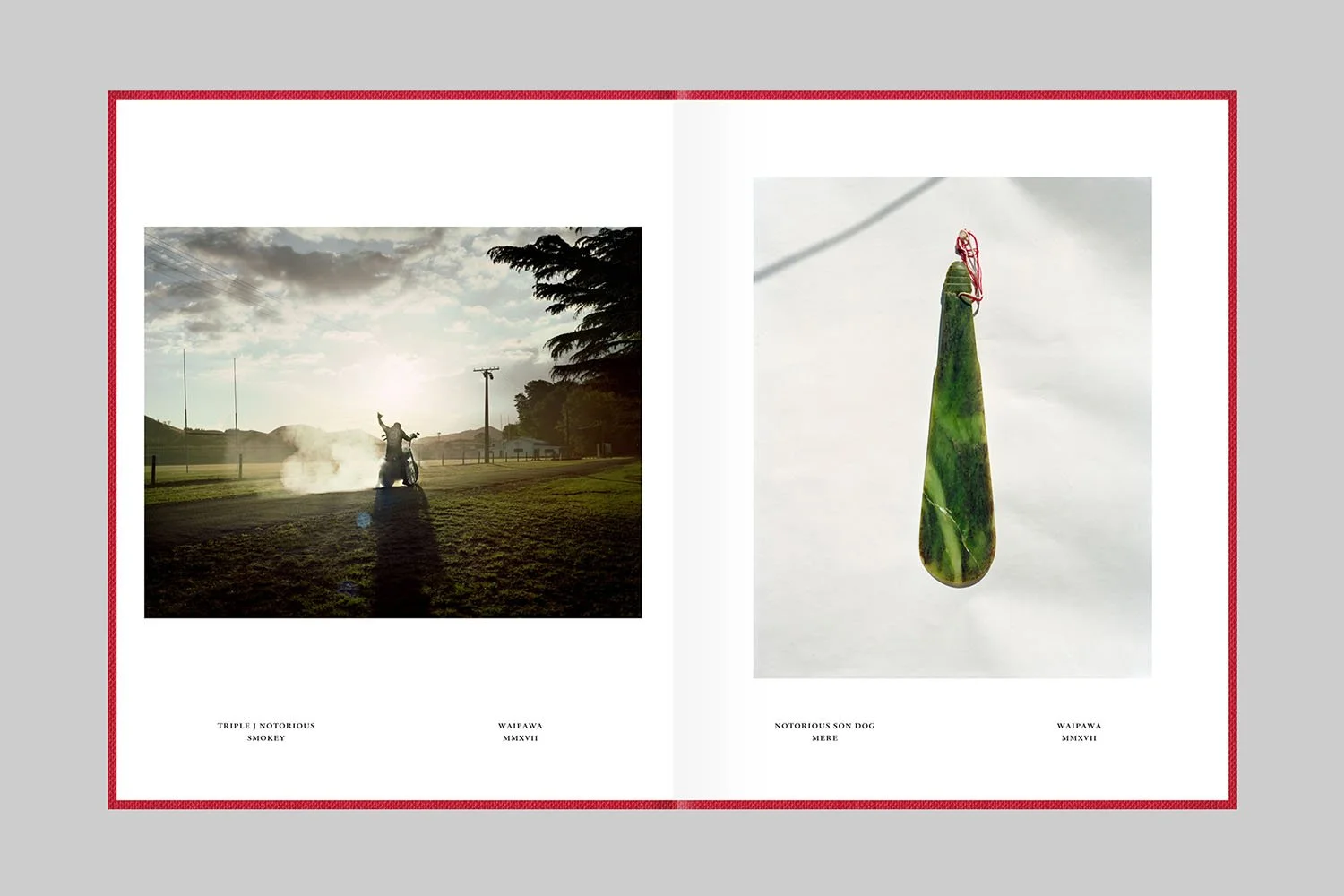

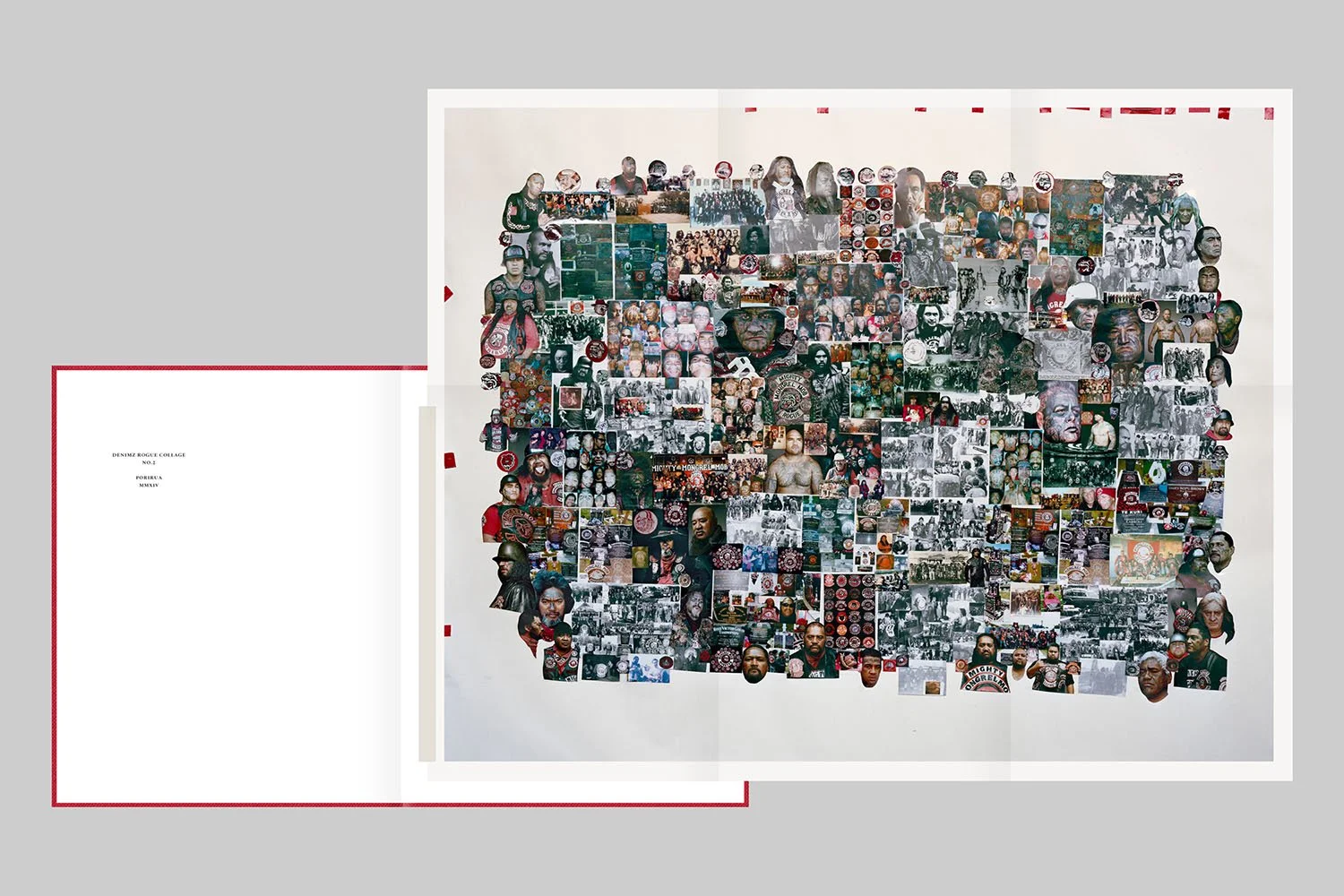

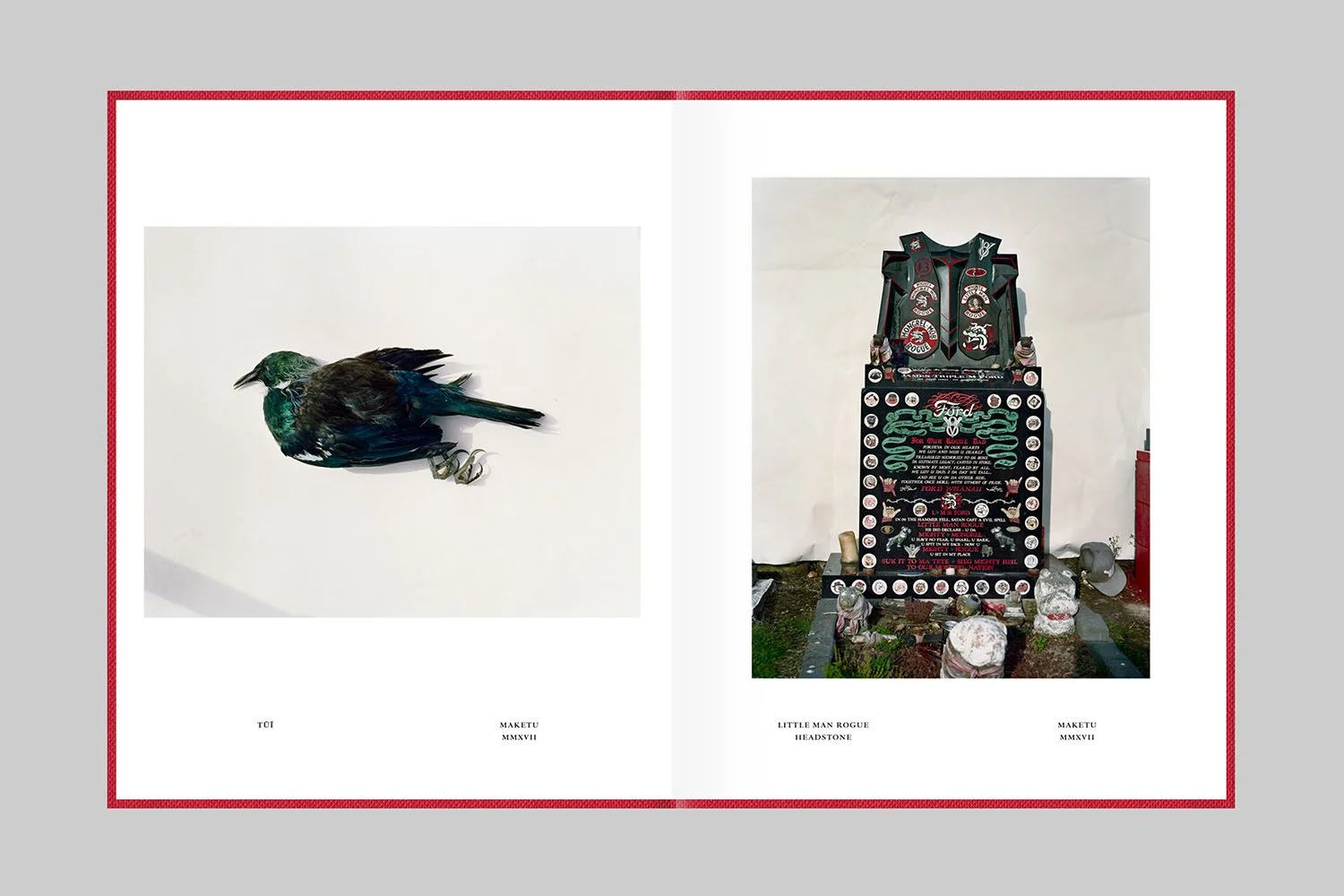

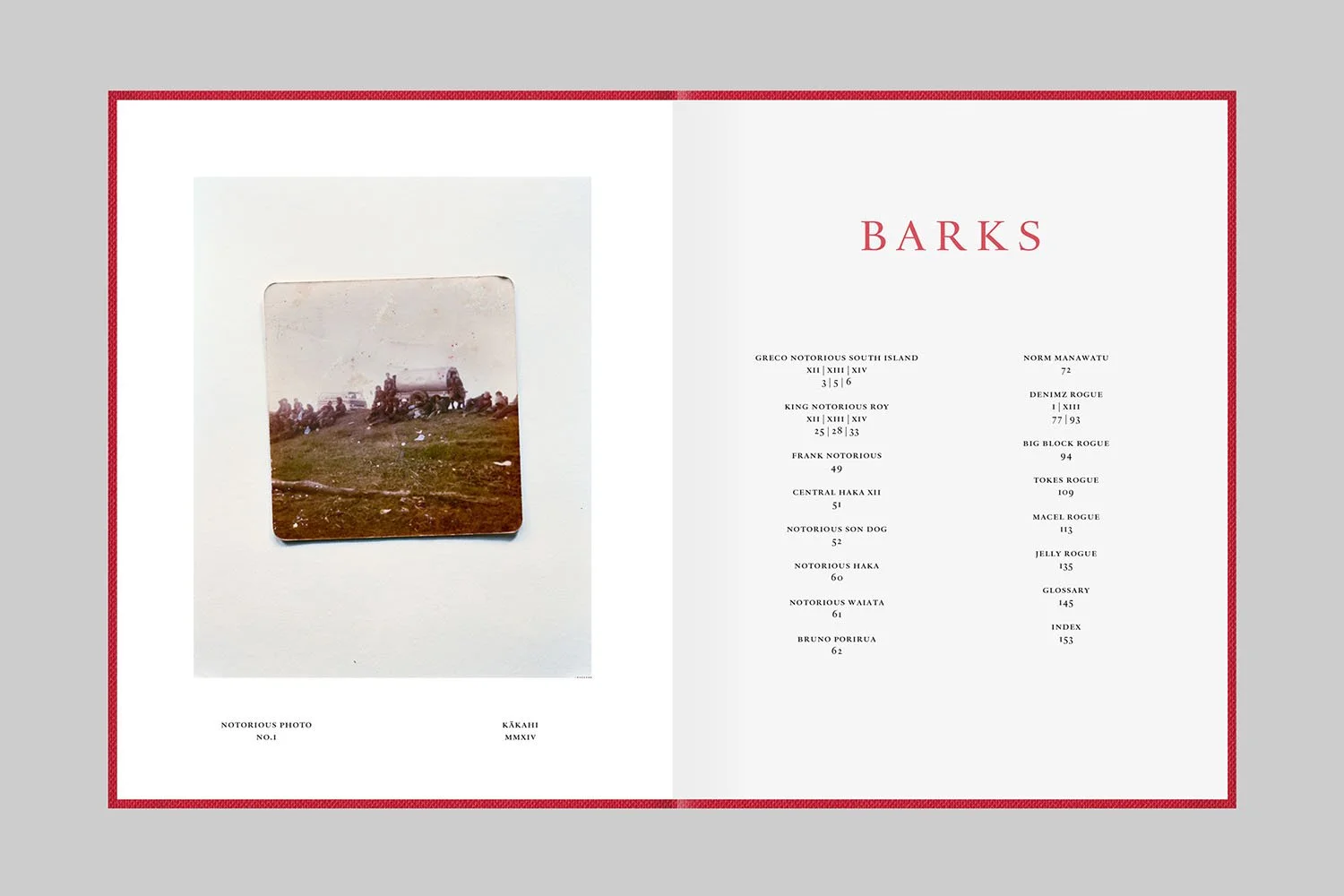

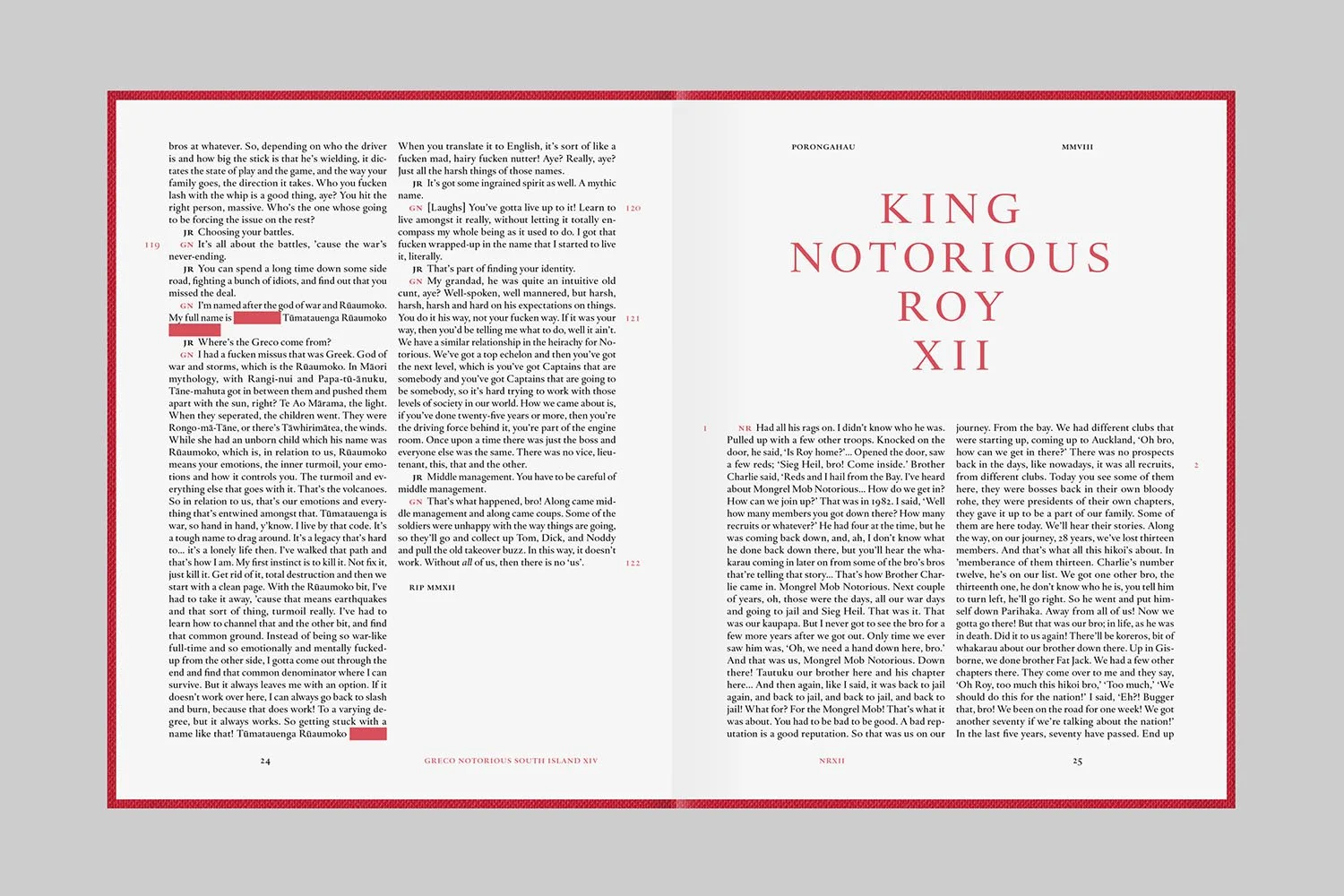

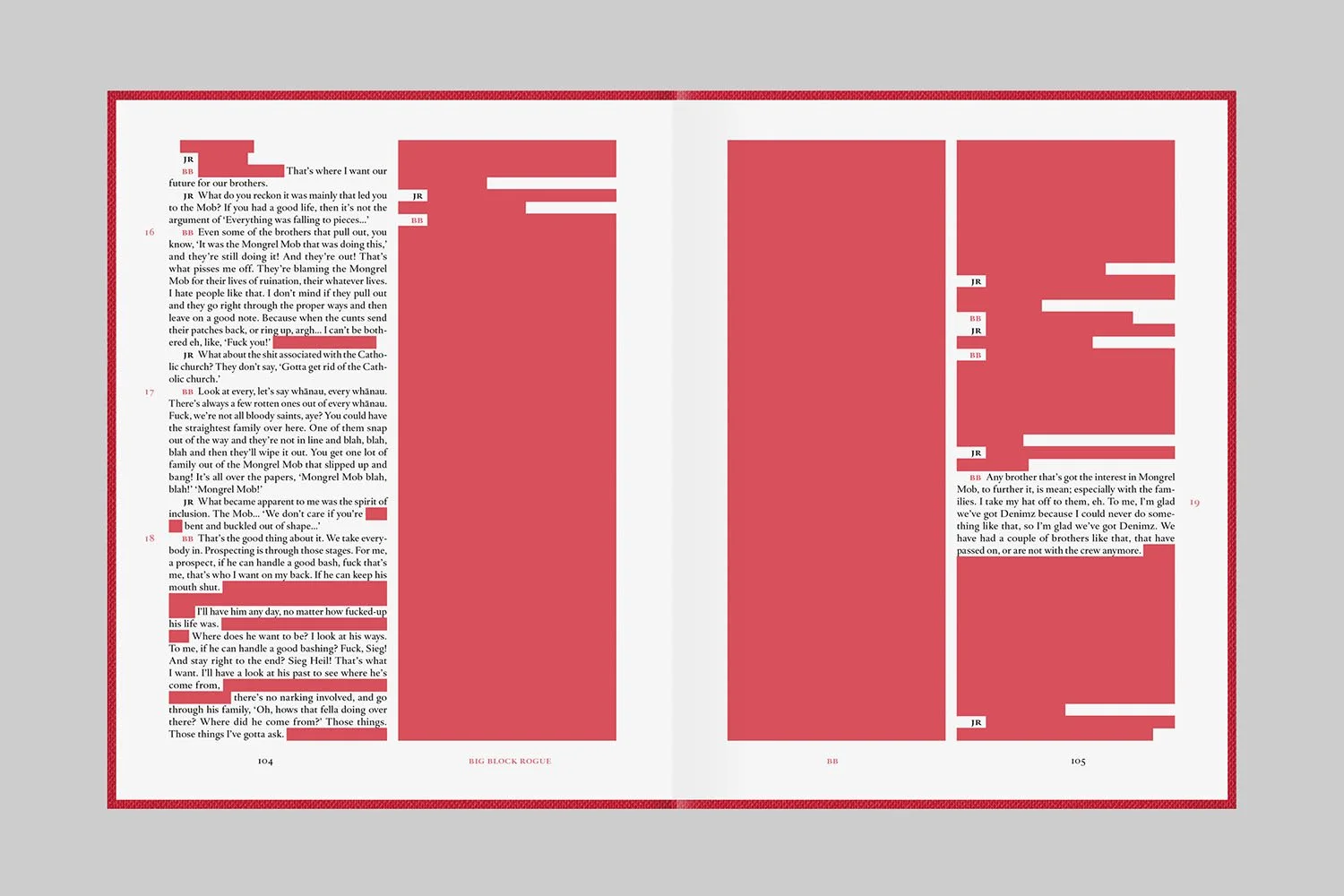

While the work has not been shown in depth outside New Zealand, Mongrelism will soon reach a greater audience as a book—made possible through support from the Book Award of the Grand Prix Images Vevey 2017/18 and published by Here Press— which will be released during the Festival Images Vevey this September. Rotman’s edit and sequencing aims to “illustrate the depth and complexity of their world, but, at the same time, give nothing away.” Though the portraits remain central, the book introduces landscapes, close-up studies of gang regalia, single vernacular images, collages hung in members’ homes, and a lengthy series of transcribed conversations between various members and Rotman. He intentionally excluded wider footage from his travels with the gang, believing that “anything that might be deduced from that material is contained within the DNA of the work I’m including. Each single image is a vessel of their entire ecology.” The book solidly affirms that the Mongrel Mob is a family. While the average person may be unable to relate to the content of the Mob’s snapshots or their tattered keepsakes, the broader corollary—family albums, inherited heirlooms, a place to call your own—is universal.

While the book is designed as a vehicle for Rotman’s work, it has also, importantly, been designed as a handbook for the Mongrel Mob community. Within the book’s fabric is an archive of genealogical, hierarchical, and geographic information. It also acts as an oral history, serving as a medium for the voices of high-ranking leaders who have since passed away. The book’s dual identity speaks to the project as a symbiotic exchange: the work fuels Rotman’s artistic vision and simultaneously links back to the community in an impactful way. A tangible metric of Rotman’s effect on the Mongrel Mob community is the integration of his photographs into their everyday lives, appearing on the walls of Mob homes intermingled with their own snapshots and even as markers on their gravestones.

A project like Mongrelism has the potential to inspire contemplation and, in the best of circumstances, challenges viewers to evaluate the nature of their entrenched values or preconceptions. While some New Zealanders may still vehemently dismiss the work, Rotman’s photographs generate dialogue and active engagement, with implications reaching beyond his depicted subject matter. And perhaps more introspective, multi-faceted conversations about these seemingly unpleasant issues will give opportunities to turn towards, with genuine interest and concern, rather than away in apathetic fear and loathing.

[1] “New Zealand has more gangsters than soldiers,” The Economist, 8 February 2018 https://www.economist.com/asia/2018/02/08/new-zealand-has-more-gangsters-than-soldiers

[2] Jarrod Gilbert, Patched: The History of Gangs in New Zealand (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2013), pp. 41.

[3] Max Kozloff, “Richard Avedon’s In the American West” from In the American West: Photographs 1979–1984 (New York: Harry N. Abrams), 2005.

[4] Nicholas Jones, “Mongrel Mob framed – in a new exhibition,” NZ Herald, 26 April 2014. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/entertainment/news/article.cfm?c_id=1501119&objectid=11244437