Tim Davis’ latest book is a visual poem celebrating Los Angeles

British Journal of Photography

July 2021

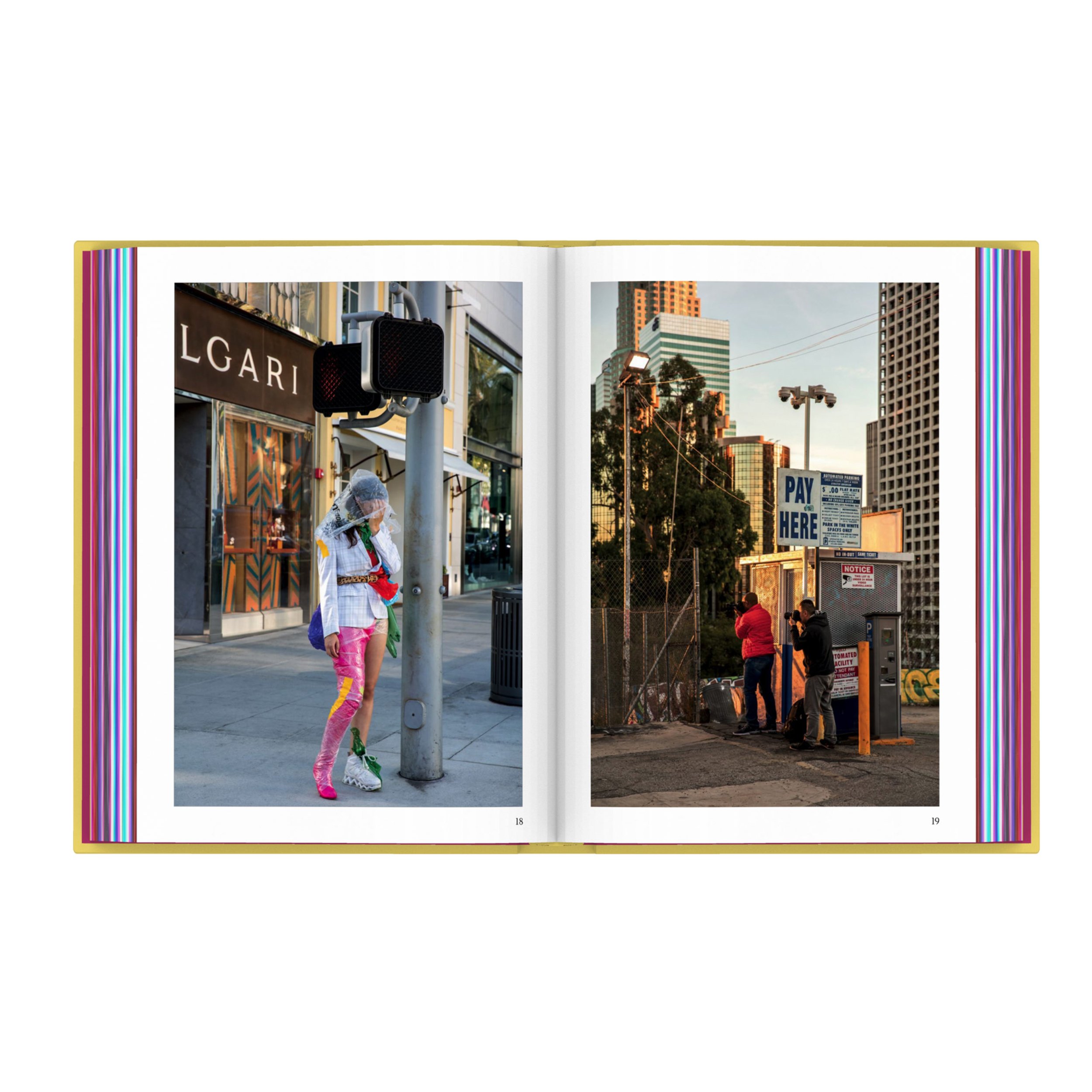

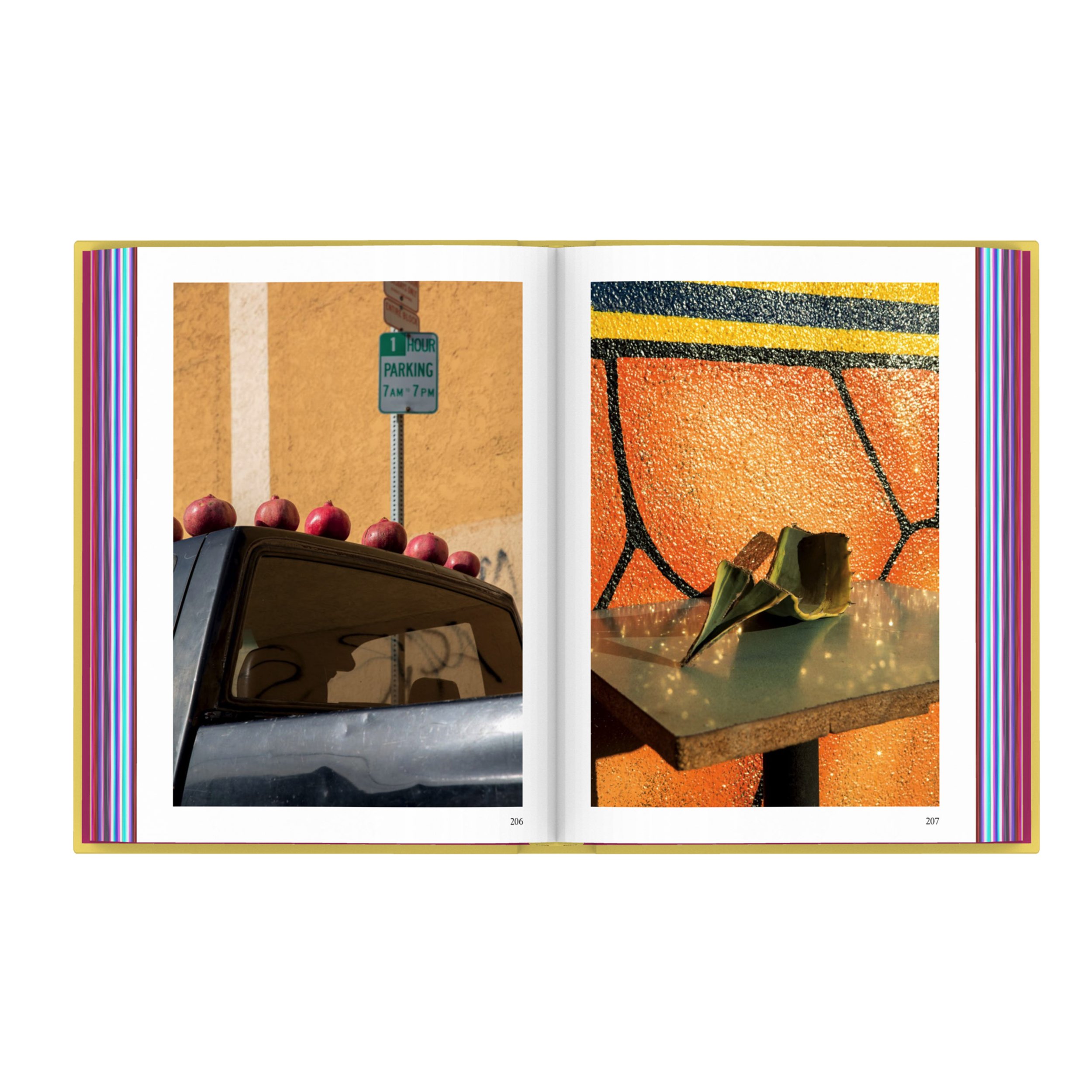

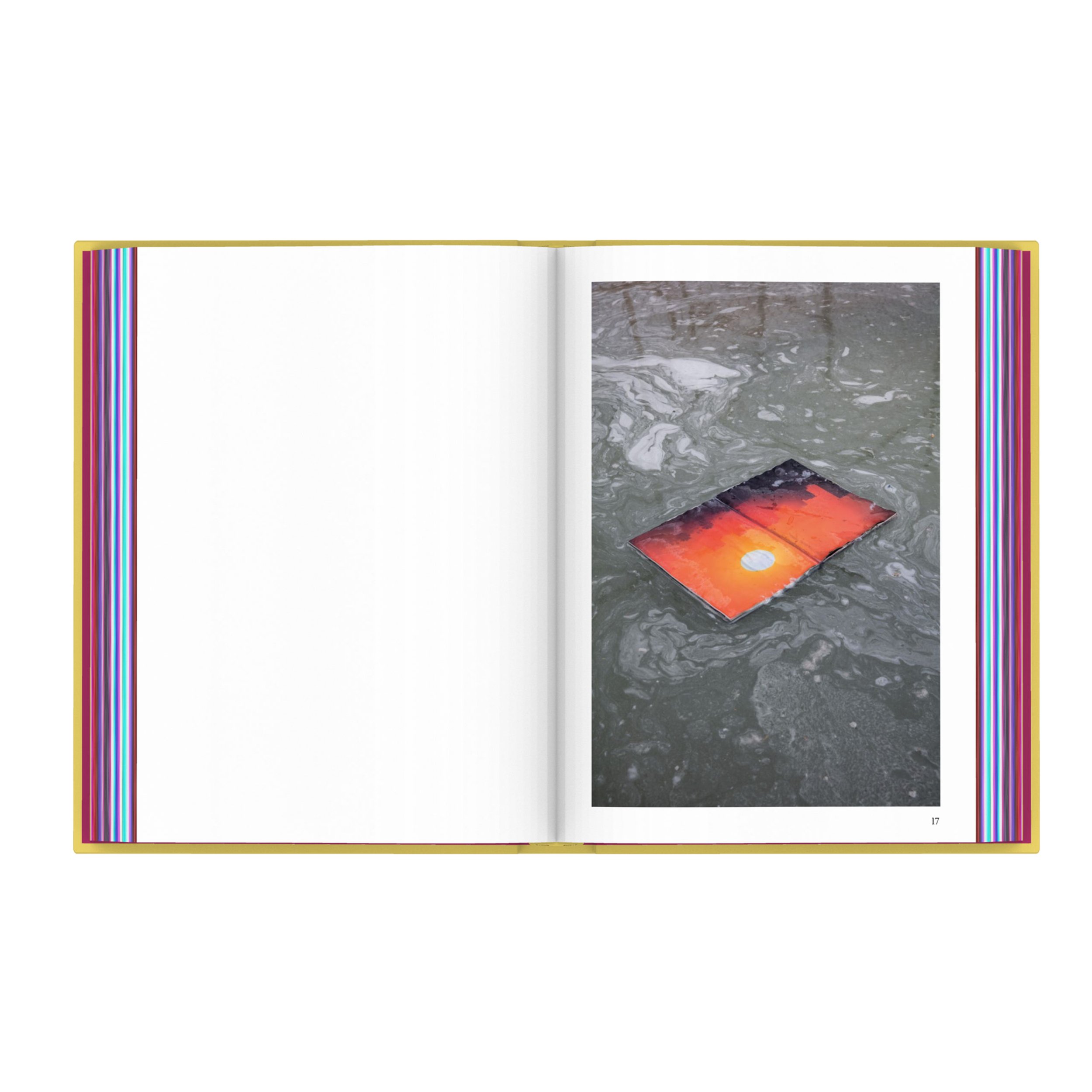

Tim Davis, from I’m Looking Through You (Aperture, 2021) © Tim Davis

“Lots of nights I went to bed in a damnably mediocre hotel unable to really remember that first camera love,” recalls photographer Tim Davis of working at his arduous project, Sunset Strips, in 2017. Hearing his malaise, his wife, painter Lisa Sanditz, urged him to “do something that will make you happy.” Davis dropped everything—“the view camera, the film, the consumable project whose artist’s statement writes itself”— and headed for Los Angeles. The city evoked “one of those dreams where you have more rooms in your apartment that you didn’t know about,” he explains. “A sense of possibility, of there being so many more pictures, so much more evocativeness and beauty than anywhere else I’d ever been.” Over the following two years, Davis returned regularly to L.A. from his upstate New York home, resulting in his expansive new monograph, I’m Looking Through You, published by Aperture.

On that first trip, Davis “decided to do everything differently, against my instincts,” he tells me. “I switched to a digital camera for the first time, I used a long 35mm aspect ratio and shot exclusively vertically, and I wandered with no set intention at first.” Though he approached his digital camera with the same diligence as his view camera, he says, “the number of different pictures I could take was invigorating.” Quickly after adopting the vertical frame format, “I began to see that way,” remembers Davis. He surveyed the city on foot—starkly contrasting car-reliant Angelinos—sometimes walking fifteen miles a day. “I found that my hunger for images didn’t slake. I couldn’t believe how much there was to see.”

“The camera only sees surfaces, and the surface of Los Angeles is an epic poem of dazzling pleasure and complication,” contends Davis. I’m Looking Through You captures the city’s diverse, sprawling physical landscape, from beaches and mountains to strip malls and residential neighborhoods. The social landscape documented is just as varied, from urban tableaux so poignant they appear staged, to Hollywood hopefuls and others so earnestly aspiring, you feel it. Davis directs his camera with an empathy rooted in genuine interest, interest in his subjects, about cultural phenomenon associated with L.A., and in the camera’s potential. Whether heart-wrenching, humorous, or anywhere between, a clear set of aesthetic concerns prevail amid these diverse pictures. A sensitivity to color, perspective, and especially light is evident. Davis waxes, “Southern California is a place where the air and light are so clear, so delicious, so advantageous to making good pictures, and that it felt like a fountain of youth. The light is like stem cells in your eyes.”

Conceived while photographing, three “story-essays” by Davis are interspersed throughout the book. These vignettes immerse you in his evolving meditations on the city, his artistic process, and the nature of photography. “I was always a poet and a photographer,” he reveals. “And language is inextricable from my photographic process.” The ubiquitous billboards and signage in L.A. fascinated Davis, who loves “seeing signage as a material thing, not digesting the message it’s sending, but unpacking how it works as an object in the world, in our lives.”

Davis’s delight making this work informs the book’s sequence and structure. “I was not interested in making a tastefully, carefully curated monograph,” he admits. “I really tried to sequence in a narrative way, telling a story as emotionally and joyously as I could, knowing it would be a little all over the place, with red herrings and miscommunications.” Together with Aperture’s Lesley Martin and designer Andrew Sloat, Davis explains, “we decided early on that the book needed to be as pleasurable to pick up and look at as it was to experience inside. We knew it needed a commercial gloss, a feeling of surface deliciousness, and it evolved over many many meetings into the object it is now.”

After a year spent largely in isolation—looking at every person, place, or object as a potentially dangerous harbinger—Davis’s book is a timely reminder of the breathtaking pleasure one can experience in approaching the world with sincere curiosity, eyes wide open, a camera in hand.